The historical correspondence course that used the postal system as the mechanism for learning material delivery and student assignment submission/return is identified by Casey (2008) as the origin of educating large numbers of, often geographically dispersed learners referred to as ‘learning at scale’.

As technology advanced so did the range of available delivery mechanisms which have, at various points, included radio, TV, video, PCs and the internet eventually resulting in a new phenomenon, when first introduced on the back of mobile internet technology in 2008, the Massive Open Online Course (MOOC). Although a fairly recent concept, the MOOC appears to satisfy large elements of Illich’s (1971) vision of a school as freely granting all students, and potential students, the facilities they require, when they require them and providing a platform for the sharing of knowledge.

Figure 2: MyEdge (2014) Massive open online courses | MOOCs Available at: http://myedge.in/blog/massive-open-online-courses-moocs/

Since their introduction, MOOCs have rapidly become a favoured distance learning model capable of granting open access to unlimited numbers of learners across a range of topics and platforms to such an extent that Daniel (2012) identified MOOCs as the year’s educational buzzword and their continued evolution in both academic and commercial education resulted in Yang et al (2014) noting that they have promptly reached an eminent position in the media, scholarly publications, and the public view.

Figure 3: EDUCAUSE SPRINT ( 2013) A short video about MOOCs and the connected age.

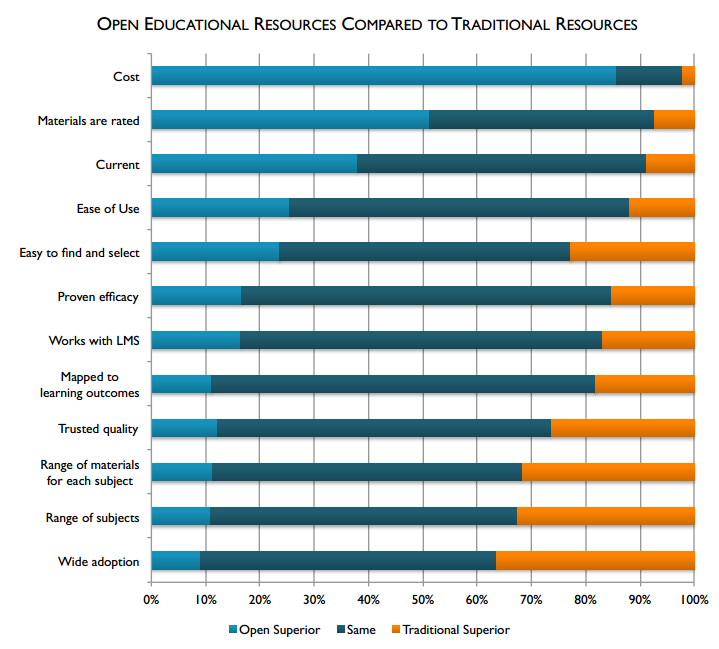

The principle of sharing digital content is not new within the Higher Education (HE) sector, dating back to the start of widespread computer usage in the 1980s, but in recent years as the growth of Open Educational Resources (OER) has gathered pace there is more desire to share resources with cost, currency and ease of acquisition and use cited among the main reasons for their adoption by Allen and Seaman (2012), albeit in a survey based on the US HE sector. According to Liyanagunawardena et al (2013), many ambitious learners become frustrated if too many OER are used within a particular educational scheme.

Figure 4: Babson Survey Research Group (2014) Open education resources compared to traditional resources Available at: http://www.emergingedtech.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/OER-babson.png.

Fini (2009) explores the concept of open access to learning being taken in a different direction after the introduction of MOOCs as typically MOOCs gather people who want to learn together with educators who seek to facilitate the process of learning.

As there has been no ‘reward’, save for the satisfaction of completing the course and personal learning, historically one of the largest challenges for MOOCs is maintaining the interest of learners who according to Towards Maturity (2014) may drop out for a wide variety of reasons unrelated to the course content and resources, clearly learning analytics has a role to play in trying to identify behaviours that are likely to result in non-completions.

Until recently this lack of reward may have been a factor for learners not completing but a number of educational establishments, including University of Leeds (2016), have recently announced an initiative in partnership with FutureLearn that would enable learners to take an extra ‘course’ after successfully completing a MOOC to allow them to earn academic credits towards a degree. As there is a shift in the role of these courses there will need to be a corresponding change in the role of data and learning analytics as the focus of this new ‘course’ will be evidencing achievement as opposed to imparting knowledge.

Reference:

Allen, I. and Seaman, J. 2012. Growing the Curriculum: Open Education Resources in U.S. Higher Education. [online] Babson Survey Research Group and Quahog Research Group, LLC. Available at: http://www.onlinelearningsurvey.com/reports/growingthecurriculum.pdf [Accessed 30 May 2016].

Casey, D. 2008. A Journey to Legitimacy: The Historical Development of Distance Education through Technology. TechTrends, [online] 52(2), pp.45-51. Available at: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11528-008-0135-z?LI=true#page-1 [Accessed 28 May 2016].

Daniel, J. 2012. Making Sense of MOOCs: Musings in a Maze of Myth, Paradox and Possibility. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, [online] 2012(3), p.18. Available at: http://jime.open.ac.uk/articles/10.5334/2012-18/ [Accessed 29 May 2016].

Fini, A. 2009. The Technological Dimension of a Massive Open Online Course: The Case of the CCK08 Course Tools. [online] 10. Available at: http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/643/1402 [Accessed 4 Jun. 2016].

Illich, I 1971. Deschooling Society. New York. Harper & Row

Liyanagunawardena, T., Adams, A. and Williams, S. 2013. MOOCs: a systematic study of the published literature 2008-2012. DOAJ. [online] Available at: http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/33109/6/MOOCs_%20AsystematicStudyOfThePublishedLiterature2008-2012.pdf [Accessed 4 Jun. 2016].

Towards Maturity 2014. Using MOOCs to Transform Traditional Training: The Role of MOOCs in Corporate Training Programmes [online] Available from http://www.towardsmaturity.org/in-focus/MOOC2014 [Accessed 12/06/2016]

University Of Leeds 2016. New online courses earn academic credits for degrees [Online} http://www.leeds.ac.uk/news/article/3870/new_online_courses_earn_academic_credits_for_degrees [Accessed 14/06/16]

Yang, D., Adamson, D. and Rosé, C. 2014. Question recommendation with constraints for massive open online courses. Proceedings of the 8th ACM Conference on Recommender systems – RecSys ’14. [online] Available at: http://0-delivery.acm.org.wam.leeds.ac.uk/10.1145/2650000/2645748/p49-yang.pdf?ip=129.11.21.2&id=2645748&acc=ACTIVE%20SERVICE&key=BF07A2EE685417C5%2EC88AFBBCE367E01E%2E4D4702B0C3E38B35%2E4D4702B0C3E38B35&CFID=622970901&CFTOKEN=94441925&__acm__=1464650727_4c41f45721f59467756bb1d42561bcfb [Accessed 31 May 2016].